Remembering The Shoah

This website evaluates the ways in which the legacy of the Shoah is memorialized on the urban fabric of Berlin and attempts to rationalize the commemoration of the Shoah within Berlin’s contemporary landscape from a geographical perspective.

DETAILS

Claudia Sternberg

4203875

L83251

THE SHOAH שואה

The origin of the Hebrew word Shoah, שואה means catastrophe, devastation or destruction and derives from the root שאה which originally meant to crash or to ruin. Shoah became the standard word to describe the Nazi regime and the mass murder of European Jews from the early 1940s. Etymologically, 'Holocaust' connotes to the biblical use of the word denoting burnt, sacrificial offerings. Shoah is seen as the most appropriate word to describe the genocide under the Nazi regime.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF MEMORIALIZATION

There is increasing geographic interest in memorials and monuments which has stemmed from a concern of remembering and forgetting the past, and methods of interpreting cultural landscapes. Memorialization occurs in spaces which are designated sites of memory and directs focus to the political nature of representing the past through the landscape. Memorials and monuments orchestrate social actors and groups to negotiate what is remembered and forgotten and therefore it is important to note that historical representation is a product of social power.

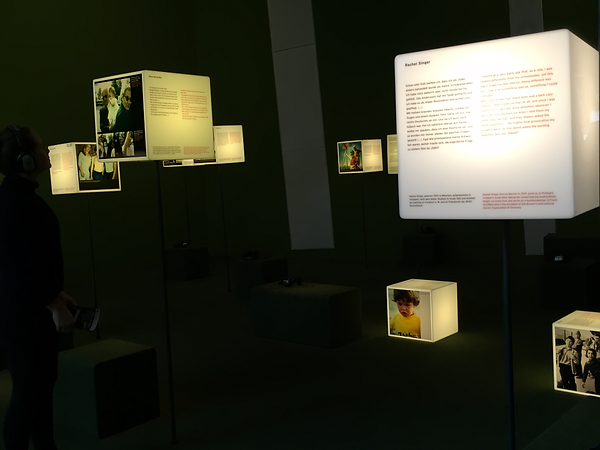

SHALECHET (FALLEN LEAVES) AT THE JEWISH MUSEUM

MEMORIALIZING THE SHOAH IN BERLIN

In order to begin the process of memorializing the destructive period in Berlin’s history, it is necessary to attempt to come to terms with what took place during the Nazi regime, although the enormity of their crimes to a large extent render all memorialization incomplete. A large part of the struggle is that a horrific event witnessing evil on the scale practiced by Nazi Germany can never be satisfactorily remembered. The implausibility and sheer difficulty of conceiving the Shoah in calm retrospect can result in diminution or even denial, and the risk of this occurring makes the commemoration of the Shoah in Berlin an even more critical and extremely necessary mission. It is of great importance for Berlin, and its future generations, to accept the Holocaust as a constant presence in German consciousness, crucially not as a source of shame and demonization of German identity, but as a matter of serious historical and ethical reflection and a reminder of the fatal and destructive impact of hate and ignorance.

There has been continuous disagreement and debate regarding the huge task of addressing and remembering the Shoah in Berlin over 70 years after it took place. There was a 17-year period of contention surrounding the proposal to build a memorial to commemorate the European Jews murdered by the National Socialist party during the Holocaust; the disagreements occurred in the context of Berlin’s struggle to identify itself following its reunification after the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The long period of disagreement reiterates the importance of memorializing past events and the necessity for memorials to endure generations through capturing and articulating memory in a relatively permanent way.

MONUMENTALITY

Monumentality is a fundamental aspect of national symbolism; monuments are traditionally defined as a structure built with the aim to preserve and cultivate the memory of an historical moment, portraying the idealized self-presentation of a nation. Often, the monuments are established to remind visitors of the country’s canonical history and do not demand the spectators’ active engagement, but serve as an exhibit.

Traditionally viewers are dwarfed by the enormity of the structure and become a passive observer of the artist’s vision rather than a participant in memory work. Monuments are very important in Berlin as Germany, in particular, has consistently relied upon grandiose national monuments to attain a sense of national cohesion and cement a German identity.

Memorialization becomes problematic when focusing on Holocaust representation as there are evident negative connotations with the capacity to taint Berlin’s reputation and impose on Germany’s historical legacy. When paying tribute to a national travesty the inherent inadequacy of conventional monuments becomes blatantly apparent. The memorialization of the Holocaust poses great challenges to traditional monuments as it is necessary to consider the paradoxical elements of embodying the causal link between the ascendance of Germany, as an all-powerful modern nation-state, and the mass murder of Jews less than a century ago. The traditional monument would be inappropriate for the circumstances of this particular memory and need to counteract the arrogance of the nation that sought to purify itself of all foreign elements.

MEMORIAL TO THE MURDERED JEWS OF EUROPE

COUNTER-MONUMENTS

The Nazis contaminated the concept of representation by using it as part of their propaganda to portray a caricature of minorities which they attempted to eradicate. Thus, it has been deemed that the most acceptable form of Holocaust remembrance is an anti-representational “counter-monument”.

Germany’s history of monumentality and nationalism demonstrates coherently as to why German artists have opposed the traditional monument as a form through which to represent the Holocaust and currently the predominant proportion of Holocaust memorials in Berlin are categorised under the rubric of “counter-monuments”.

The effacement of traditional form toward counter-monuments stimulates continued discussion, opens up the memorials to further interpretation, analysis and debate. The memorial is against itself in its manifested form to the degree that the object has a malleable meaning and definition, despite being concrete and permanent in form, and memorials are created with the purpose of inducing contrasting emotions and provoking further questions to aid the understanding of the events occurring during the Shoah.

QUOTE

“Each memorial object also has a prehistory and an afterlife, neither of which is very visible when simply looking at the memorial itself."

- Jordan, 2006:96

The original and perplexing structures, void of words and pictures, serve to illustrate central themes in German collective memory and encourage spectators to engage with the history of the Holocaust, as well as try to compherend the guilt that has become inherently embodied in the fabric of Berlin. This ensures that the process of remembering is strenghtened and accessible to a range of people and thus the experience of remembering the Shoah in Berlin becomes a myriad of possible interpretations.

The predominance of counter-monuments in modern Berlin is a consequence of the 20th century reaction to the Holocaust in which many struggled to deal with the guilt and blame. The memorialization of the urban landscape has ultimately been successful in embodying the ambivalence felt by German’s toward the memory of the Holocaust. The complexity of navigating memorialization provides a platform for discussion on the ways in which the past should be represented in a city and the making of memorials in a city landscape is part of the active process of sense-making of history through time.